28 March 2024, this blog is about writing in scenes. I’m focusing on the tools to build scenes. I’ll leave up the parts of a novel because I think this is an important picture for any novelist. I’m writing about how to begin and write a novel.

- The initial scene

- The rising action scenes

- The climax scene

- The falling action scene(s)

- The dénouement scene(s)

Announcement: I need a new publisher. Ancient Light has been delayed due to the economy, and it may not be published. Ancient Light includes Aegypt, Sister of Light and Sister of Darkness. If you are interested in historical/suspense literature, please give my novels a try. You can read about them at http://www.ancientlight.com. I’ll keep you updated.

Today’s Blog: The skill of using language comes from the ability to put together figures of speech that act as symbols in writing.

Short digression: Back in the USA. I didn’t update you on all my travels, but I basically went all through Italy and Greece as well as a sidetrack to Malta. I’m back.

Here are my rules of writing:

1. Entertain your readers.

2. Don’t confuse your readers.

3. Ground your readers in the writing.

4. Don’t show (or tell) everything.

4a. Show what can be seen, heard, felt, smelled, and tasted on the stage of the novel.

5. Immerse yourself in the world of your writing.

6. The initial scene is the most important scene.

Creativity is the extrapolation of older ideas to form new ones or to present old ideas in a new form. It is a reflection of something new created with ties to the history, science, and logic (the intellect). Creativity requires consuming, thinking, and producing.

Scene development:

Here is the beginning of the scene development method from the outline:

1. Scene input (comes from the previous scene output or is an initial scene)

2. Write the scene setting (place, time, stuff, and characters)

3. Imagine the output, creative elements, plot, telic flaw resolution (climax) and develop the tension and release.

4. Write the scene using the output and creative elements to build the tension.

5. Write the release

6. Write the kicker

First step of writing—enjoy writing. Writing is a chore—especially if you don’t know what you are doing, and you don’t know where you are going. Let me help you with that.

Today:

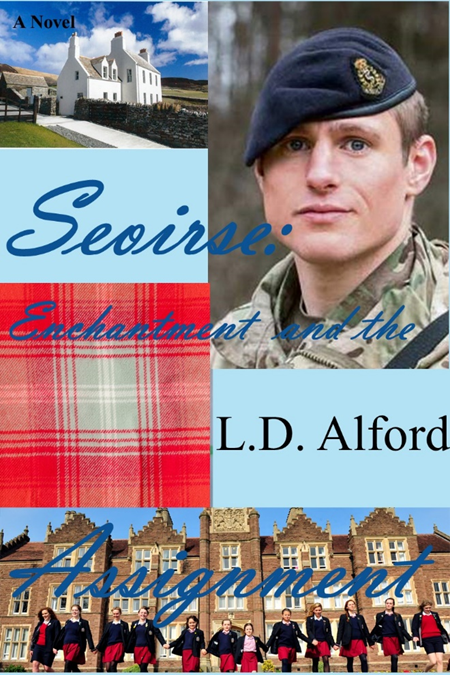

These are the three novels I’m contemplating writing. I finished Seoirse, and I developed these protagonists and the protagonist’s helpers for the other novels.

For novel 34: Seoirse is assigned to be Rose’s protector and helper at Monmouth while Rose deals with five goddesses and schoolwork; unfortunately Seoirse has fallen in love with Rose.

For novel 35: Eoghan, a Scottish National Park Authority Ranger, while handing a supernatural problem in Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park discovers the crypt of Aine and accidentally releases her into the world; Eoghan wants more from the world and Aine desires a new life and perhaps love.

The first or initial scene is what we work hard to start out our novels.

A scene always starts with the setting elements. Look at the scene development outline:

1. Scene input (comes from the previous scene output or is an initial scene)

2. Write the scene setting (place, time, stuff, and characters)

3. Imagine the output, creative elements, plot, telic flaw resolution (climax) and develop the tension and release.

4. Write the scene using the output and creative elements to build the tension.

5. Write the release

6. Write the kicker

If you notice, the first thing we write is the scene setting. You can continue setting development through the scene, but every scene should start with the setting. You must set the stage of the novel with the scene setting.

In the first place, without setting elements, you can’t write anything. You must introduce setting elements to be able to have action and dialog. The setting elements usually come out of narration of some type.

Every creative element should also be a plot element. If they are not, you should not make them a creative element.

This means the plots must further the telic flaw resolution and nothing else. A plot element can become a telic resolution element. However, I should write, a plot element should always become a telic resolution element.

I’ve never put this completely together before. Here’s a chronological list of my novels:

The Second Mission (399 to 400 BC)

Centurion (6 BC to 33 AD)

Aksinya: Enchantment and the Daemon 1917 – 1918 (1920)

Aegypt 1926

Sister of Light 1926 – 1934

Sister of Darkness 1939 – 1945

Shadow of Darkness 1945 – 1953

Shadow of Light 1953 – 1956

Antebellum 1965 (1860 to 1865)

Children of Light and Darkness 1970 – 1971

Warrior of Light 1974 – 1976

Warrior of Darkness 1980 – 1981

Deirdre: Enchantment and the School 1992 – 1993

Cassandra: Enchantment and the Warriors 1993 – 1994

Hestia: Enchantment of the Hearth 2000 – 2001

Essie: Enchantment and the Aos Si 2002 – 2005

Khione: Enchantment and the Fox 2003 – 2004

Blue Rose: Enchantment and the Detective 2008 – 2009

Dana-ana: Enchantment and the Maiden 2009 – 2010

Valeska: Enchantment and the Vampire 2014 – 2015

Lilly: Enchantment and the Computer 2014 – 2015

September 2022 – death of Elizabeth

Sorcha: Enchantment and the Curse 2025 – 2026

2026 death of Mrs. Calloway

Rose: Enchantment and the Flower January to April 2028

Seoirse: Enchantment and the Assignment August to November 2028

science fiction

The End of Honor

The Fox’s Honor

A Season of Honor

Athelstan Cying

Twilight Lamb

Regia Anglorum

Shadowed Vale

Ddraig Goch – not completed

What’s the point? I just wanted to list all my novels in chronological order. I’m not sure where I’m going from this, but I thought it was a fun idea. I didn’t put in the dates of the science fiction because although it is possible to figure them out, they are pretty esoteric. All the other novels are connected in history and time.

I’ve developed the protagonist and the focus of the novel. I’ve been through the plots and all the basics of the scene development and what I’d generally like to include in this novel, Aine. I’m not really ready to start writing because I’m supposed to be focusing myself on getting a new publisher or an agent—I’m going for an agent at this time. To me, writing is easy, the getting a publisher or an agent is the hard part. And, I have 32 novels to sell, oh well.

I’m cleaning up the breadcrumbs from the development of Aine. If you notice, I’ve already written novel 34. I also wrote that I have 32 completed novels. I’m missing two—nope, not at all. My numbering scheme just has two incomplete novels that I still intend to finish, but that I haven’t been writing on for a while. I usually complete a novel before moving on, but I didn’t finish those two. They have great potential, but my interest waned a little and I lost my focus. I never had writer’s block. Ha ha.

That was my point before. You can’t have writer’s block if you are imagining your storyline and plots first and then using your creativity to write the story next. It is impossible to have problems with ideas—you can however, have problems with the writing itself. This is a real problem and one specifically of skill and practice. That’s something I should go over again. I’m not sure where to start, but perhaps I should start with the most basic part of writing—the sentence and then move to the paragraph.

I don’t intend to go over every individual part of speech and of writing, but I do intend to hit the most important parts for the writer and for writing novels. So, get ready. We are moving to the sentence.

If you don’t understand grammar and the sentence, then this is something you need to really get down. If English isn’t your first language, then you really need to study it hard. The easy part about writing in English is all you need is the past tense for the narrative and action and the present tense for the dialog. Easy, right?

The problem is that with the present tense and the past tense, there are a whole host of other tenses in English. It ain’t that simple, and the fiction author needs to be aware and actively engaged in the language. As I noted, most of the narrative will be in the past tense, hopefully the third person past tense, while most of the dialog will be in the present tense, much of that will vary between first, second, and third person. And the real problems begin with future tense and the present participle. Yeah yeah yeah, I’m not going to go into all those verb tenses and I’m not going to get into the details of sentence construction except to write this. Here are some really important rules of sentence construction for writers:

- Narrative should be past tense.

- Dialog should be present tense.

- Stay away from passive voice. There are reasons for using passive voice, but there ain’t that many. Use active voice.

- When moving into the past you can use the past perfect, but get back into the past tense as quickly as possible. Keep out of the past perfect as much as possible.

- Keep it simple. This is especially true of verb constructions and sentence construction.

- Don’t write run-ons. Break up sentences for more simplicity.

- However, keep it together. The proper use of conjunctions and connected clauses is an indication of writing skill. Too much is bad too little is bad.

- Use sentences to indicate action and pace. This is getting into the complexities of writing.

- Short sentences indicate fast pace and action.

- Longer sentences indicate less action and slow pace.

- Short sentences indicate terse writing, and many times incomplete thought.

- Long sentences indicate boring writing and too much telling.

- Show don’t tell.

- More dialog is showing—less dialog is telling.

- More action is showing—more narrative is telling.

I’m sure there is more, but I’ll end it here and unless I think of something really important about sentences, I’ll move on to paragraphs.

If you can’t write a strong sentence, you can’t write. However, if you can’t write a good paragraph, you definitely can’t write. I think in seventh grade the world of English was all about writing a paragraph. Unfortunately, I don’t think they really taught correctly about how to write a good paragraph. They just had us students write paragraphs. The practice was great, but it could have been so much more. I do think that year of writing paragraphs really helped me as a writer, but at the same time, it could have been much better. I’ll give you the real education.

In the first place, all paragraphs follow the same rule—that is except the dialog paragraph in English. I’ll mention that at the end, but for now realize we are writing about general paragraphs and especially those in actin and narration as opposed to those in dialog. In dialog, the longer thoughts and ideas do still follow these basic rules of the paragraph. Let’s look at paragraph structure.

All paragraphs have this structure:

- Topic sentence with a potential transition from the previous paragraph

- Body of the paragraph explaining or expanding the topic

- Conclusion of the topic and transition to the next paragraph

This is the basic structure of every paragraph. If you follow this, you will know where to start and stop your paragraphs, your writing will be readable and understandable, and your writing will make sense.

When I was learning to write, the biggest problem I had with the paragraph was where to begin and where to end. Most people had a similar problem with the sentence. That’s why so many youthful writers can’t stop their run-ons. If you know the basic rules about the sentence, you will get rid of your run-on problem. If you know the structure of the paragraph, you will fix your paragraph problem. Topic, body, conclusion and transition. That’s it. Each new topic needs a new paragraph. I’ll get to that, next.

With a paragraph, the most important point is to introduce the topic of the paragraph and continue to write until the next topic. Close the paragraph and transition to the next topic. I’ll give an example:

The once Shiggaion Tash, now Shiggy Tash, stepped out of her small and ancient Triumph touring car. She clutched her gold Gucci bag closer to the heavy black Givenchy coat that covered her short blue Zuhair Murad skirt. It was freezing and the short skirt didn’t help much, but that was a necessary inconvenience when she needed constant access to her special, um, gear. She gazed up at the whitewashed brick side of Viera Lodge and shrugged. It was the best The Organization could do on short notice, and in this area.

Actually, the house was remarkably nice for the Scottish Orkney Islands, and especially for tiny Rousay Island in particular. She’d memorized everything about it. It should be very pleasant if all the information she received was correct. The house was newly refurbished around 2024. There was a garage, but she didn’t trust them during operations. Perhaps if she had a second vehicle. She glanced back at the tactically parked Triumph, and mouthed, “Old Scorch, you’ll have to make do with the cold.”

The house was two storied and pretty ancient. She knew it was originally built around 1836. It possessed a section at this side that held the kitchen with a large new bath above. Every external wall of the house was freshly painted white, she had guessed whitewash. In the setting winter sun, it certainly looked like whitewash, at least under the brilliant orange reflection of the sun.

These aren’t that complex in terms of paragraphs, but they should do. Note, the topic of the first paragraph is Shiggy. Here’s the topic sentence: The once Shiggaion Tash, now Shiggy Tash, stepped out of her small and ancient Triumph touring car.

The paragraph continues about Shiggy until we reach the last sentence: She gazed up at the whitewashed brick side of Viera Lodge and shrugged. It was the best The Organization could do on short notice, and in this area.

Notice, this sentence if still about Shiggy, but it transitions to the house. It give us some information about where Shiggy is and where the house is. The next paragraph picks up the topic: Actually, the house was remarkably nice for the Scottish Orkney Islands, and especially for tiny Rousay Island in particular.

This is all about the house and it’s location, but it also reveals information about Shiggy. This continues until the transition. This is an advanced transition that brings in more information, but turns us back to the house: She glanced back at the tactically parked Triumph, and mouthed, “Old Scorch, you’ll have to make do with the cold.”

This is also an example of using dialog and turning to the use of dialog or really the proper grammar of dialog to make a paragraph. The paragraph indeed transitions, but we use the rule of dialog here to force the transition. The transition is real and moves back to the house, but the rule of dialog grammar and punctuation forces us to a paragraph ending. The next paragraph has a topic sentence: The house was two storied and pretty ancient.

We get a paragraph completely about the house and its description from the outside. The transition sentence closes this paragraph and points to the next: In the setting winter sun, it certainly looked like whitewash, at least under the brilliant orange reflection of the sun.

The next paragraph will tell us about the area around the house and the setting for the house. This is how we write paragraphs. We don’t need to get all strict and outliney detailed about them, we just write them and keep them on topic. Where most have problems is when the paragraphs start to get to a full page or they seem too long—they are. Break them up by topic. Make nice transitions. Make it all sound good and fit together. I’ll look at this and at dialog paragraphs next.

Yes, there is much more about paragraphs. The main point is the idea of the topic and the topic sentence. If you can grasp this and keep this on track, you usually can write a good paragraph. At the moment, I want to mention about dialog and the paragraph. This is an important grammar point in English. Once we cover this, we can go back to the basic paragraph and paragraph structure.

In English dialog, each speaker is delineated by a new paragraph. This is a rule of grammar, but it makes sense: the next speaker provides a potential new topic because they are the next speaker. Actually, the topic is immaterial in the case of dialog, at least at this point. What is important in English is to denote the next speaker. Here’s how it looks on paper (eather).

Jane flicked her fingers, “I don’t like it at all.”

John stared her down, “It doesn’t matter what you like or don’t like.”

She squinted at him, “Don’t speak down to me.”

Pretty much the same topic, but each sentence is a new paragraph. That’s just how English grammar works. Now, with that same speaker, when they are speaking and come to a new topic, the rules are a little different. If you break a paragraph in the middle of a dialog, you don’t close the quote, and you start a new paragraph with a quote. Here’s what it looks like:

Dave scratched his nose, “I’m not sure I like this house. It’s dismal, ugly, and too far from town to be of any use to us. I’m not sure I can even get to work on time unless I get up at two in the morning.

“On another note, the car is acting up and I need to get it into the shop.”

This happens rarely, and is a bit of a bother to many readers and writers, but if you need to break the paragraph in the middle of a dialog, you don’t close the quote and then you continue with a new paragraph—the same speaker is still speaking. Actually, a better way to write this, might be:

Dave scratched his nose, “I’m not sure I like this house. It’s dismal, ugly, and too far from town to be of any use to us. I’m not sure I can even get to work on time unless I get up at two in the morning.”

Dave continued, “On another note, the car is acting up and I need to get it into the shop.”

Either way can be a bit confusing to the reader, but the second is less confusing. Either way is acceptable in English grammar. Back to the paragraph and structure, next.

As I wrote, paragraphs are topical. They have a very specific but very open form. That may be why many people are confused about them, even teachers. When I was a student (a kid) none of the explanations by my teachers about the paragraph resonated with me. I found their explanations to be unusable and not understandable. Today, I think I understand them very well. I come to a full understanding of the paragraph. I don’t remember when this came to be, but I can assure you, it was when I was trying to hack through some fiction and likely a novel. The realization was enormous. If my teachers had taught me then, I might have even been a better writer earlier. Still, I’m happy with my progress, and I’d like no one else to be confused by the idea of the paragraph because the paragraph is fundamental to writing, in general.

Words are the basic elements of writing. Sentences are the basic forms of thought. Paragraphs are the fundamental parts of putting ideas into sentences that are formed by words. The paragraph is the most elemental form of ideas. You can’t write without a grasp of the three. The most important part of paragraphs is that they are the building blocks of the scene. We can almost make an outline of a scene by paragraph. Such a scene would be way too short, but you can do it. The main point is that I want to get us to the point of the scene. The scene is the fundamental and simplest part of a novel. A novel can’t be written without scenes and scenes are the novel. With this review:

All paragraphs have this structure:

- Topic sentence with a potential transition from the previous paragraph

- Body of the paragraph explaining or expanding the topic

- Conclusion of the topic and transition to the next paragraph

We can move to the most important part of any fiction or of the novel: the scene.

As long as you know how to write an effective paragraph, we can move to the scene. Look aback at the paragraph structure and write your paragraphs in this way every time. This is the way we write. The scene, however, is the main element of the novel. Let’s just say, we can’t write any fiction without a great scene. That normal novel is based on the scene. We write scenes to drive the plots and the telic flaw resolution.

Here is a basic scene outlive for a normal novel:

1. Scene input (comes from the previous scene output or is an initial scene)

2. Write the scene setting (place, time, stuff, and characters)

3. Imagine the output, creative elements, plot, telic flaw resolution (climax) and develop the tension and release.

4. Write the scene using the output and creative elements to build the tension.

5. Write the release

6. Write the kicker

Yes, I’ll got through this again and put it in the context of the novel. We’ll see how it all works together.

I’m of the opinion that if you can write a good paragraph with good sentences, you can simply follow the scene outline to write a great (good) scene. There are a lot of ifs in this paragraphs.

There is a presumption in this outline—the first is the initial scene. The initial scene implies you have a protagonist, an antagonist or protagonist’s helper, an initial setting, and a telic flaw. I’ve gone through this before. I’ll do it again, but not at the moment. Perhaps as we delve into the scene outline, I’ll provide some more of this information in depth, but I’d like to give you a wider field of ideas at the moment.

In the first place, we need an initial scene to set off the novel. That initial scene must (should) include your initial setting, the protagonist, the antagonist or the protagonist’s helper, and a telic flaw. With these you can write a novel. As I’ve written before, these are critical as well as important items in the initial scene and in your novel. I personally develop the initial scene in my imagination and then populate it with the proper elements later. To me the initial scene itself is the main and most important part of the novel and of the development of the novel. Everything else can be developed in a more rigid and organized fashion—the initial scene can’t be. It must be visceral and real. The initial scene, more than any other scene, must catch the attention of the reader and the writer. The reader and publisher for sales and acceptance, the writer to catch fire to the novel.

The initial scene defines the novel. I see the initial scene in my imagination. It might be blurry and not totally defined, but the point of the scene is to launch the novel and nothing else. Eventually, the initial scene must have pure clarity and beauty, but in the beginning, it can be like an ancient mirror, through a glass darkly. I’ll continue this thought with an example, next.

I’ve written about this example before. I’ll do it again. When I developed my novel Essie: Enchantment and the Aos Si, I pictured an abused, naked, and feral girl who only ate meat and who was raiding Mrs. Lyon’s pantry. This picture for an initial scene is what motivated and developed this novel for me—in other words, I had to develop everything to support this initial scene. To me, the scene itself was worth writing about and then developing to build a novel. There are obvious questions such a scenario and scene bring up. Why was the girl abused? Who is she? Where did she come from? Why is she naked? Why is she wild? Why won’t she eat anything except meat? Why is she in Mrs. Lyon’s pantry? Where did she come from? There are other important questions that come from this situation and scene as well. You might write an entirely different novel based on a similar type scene. In any case, the scene itself, for me, drove the novel and the ideas for the novel. In this case, I built up an initial scene that I thought would sell a novel all by itself. This is my tactic in writing everything I write. The point is the initial scene. The rest of the novel is important and fun as well, but the initial scene is what sells your novel. Plus, the initial scene, for me, writes the novel. I have other examples. I’ll give you one from Seoirse, next.

In Seoirse, I planned an initial scene where Rose confronted the dangerous goddess girls and that caused and set off the entire novel. I couldn’t make it an initial scene. There was too much build-up to the scene for it to be an initial scene. Even if I made Rose the protagonist, it just wouldn’t work. Plus, Seoirse as the protagonist was just the best choice especially to balance Rose and her issues.

In any case, although I wanted the confrontation scene to be the initial scene, it wouldn’t work, and I’m not into flashbacks—especially for very important scenes. I’m not into flashbacks at all, they are useful, and can be effective, but I don’t use them and I don’t recommend them. An initial scene as a flashback would be horrible.

So, in Seoirse, I was thwarted in developing the initial scene, but I did better—I went to my own advise and made the initial scene the initial meeting of the protagonist, Seoirse, with the protagonist’s helper, Rose. That fixed everything. This scene really set off the novel and allowed me to develop the buildup to the scene I originally envisioned. I think I showed this on this blog and definitely on my other blog, as I developed the novel and explained the development.

The main point of this is to envision the initial scene. That means to imagine it, and imagine it well. Then start with it. As I wrote, I couldn’t make the initial scene of Seoirse work as I desired, but I could build it from another scene, and a better initial scene. That’s how we use our imagination to develop scenes and an initial scene. I’ll also point out that at no time did I have any writer’s block—that’s because I imagine and worked out everything in my imagination and mind before I sat down to write. We’ll look at elements of the initial scene and scene development, next.

Here is the scene outline:

1. Scene input (comes from the previous scene output or is an initial scene)

2. Write the scene setting (place, time, stuff, and characters)

3. Imagine the output, creative elements, plot, telic flaw resolution (climax) and develop the tension and release.

4. Write the scene using the output and creative elements to build the tension.

5. Write the release

6. Write the kicker

The initial scene doesn’t have an input. We need to develop the entire prescene information. This many times isn’t expressed in the novel, not directly. This preinitial scene information becomes part of the revelation of the protagonist. We give this out as necessary. For an initial scene, we start with the minimal information. We want to give the basics of the setting. I’ll get to this next.

I’m flying out to Iowa to pick up kids and grandkids. So, I’m writing at 9000 feet over Missouri. This is very pertinent to the scene and setting the scene. In a novel, if I just started writing about the character flying, but I never told you he or she was flying, you would be completely lost for a long time—lost long enough to perhaps throw away the book in disgust. It would irritate me.

This is one of my pet peeves with any and all writers. Most published and experienced writers set the scene properly and develop the novel properly, but some, especially the inexperienced act like they are playing I got a secret. In fact, there was a whole period in especially science fiction where the authors kept close hold on the setting and details of the setting as if that was a real secret to be revealed. The setting is never a secret.

In every stage play anyone has ever seen, the setting or at least the details of the stage are evident the moment the curtain rises. This is how novels should work. The moment the curtain rises, the reader should see the stage and everything on it. Now, in writing, we can release the information as we desire. If we want to describe or focus on one specific part of the stage first, we can. I advise a reasoned and logical progress in the description, but, yes, for entertainment purposes, you can and should emphasize the setting in a way that is fun and builds tension. The main point is we are not playing I’ve got a secret with the setting, although some elements might be kept under wraps.

I started Sorcha: Enchantment and the Curse with great scene setting, but the protagonist had no idea where she was or even her state. She woke up from anesthesia strapped to a table with no idea how she got there, why she was there, or where she was. That was part of the initial setting and scene. I didn’t play secrets with the reader, I showed the reader the scene setting, but all the other information was what the protagonist knew. This is the real strength of the setting. I’ll get to that, next.

We show the setting and then set in motion the situation. The point, in the initial scene, is to develop the setting and describe the setting with sufficient setting elements that can be turned into creative elements as well as to set the scene. This is why I advise setting the scene as the first step in writing any scene. All you have to do is to show what your readers can see on the stage of the novel. Showing what can be seen is the main point of scene setting. The important point is showing what the readers can see. This is just like a stage play.

When the curtain rises, the audience can see the stage. They have no idea about the characters or what anything means except from what they see on the stage. For example, if the stage shows a castle interior, the viewers might gather something about the place. If the stage shows a train station with a German name, that tells us a little about the setting. If the setting shows an opulent mansion with people in 16th Century costumes, that tells us a lot about the place. If a character begins to speak about some king, that places the setting even better. The main point is that the author without telling can show and place a lot into the setting, and the readers will understand and begin to understand the situation. With dialog, as I wrote, we can further set the time and place, we can and should do this without telling.

So, the initial thing in any setting is to describe the stage and everyone and every thing on and as they enter the stage. It isn’t necessary to describe every single thing on the stage, but to build it up as the readers need the information. This is bringing in setting elements that then we make into creative elements. I’ll write about this, next.

Set the stage of the novel, and show don’t tell. Show us what is on the stage when your novel starts. Give us good, useful, and elegant descriptions of every thing that is important. This creates setting elements. In addition, show us the people and what they are wearing.

Show us the place and the time—don’t tell us anything, show everything. Once you’ve set the stage, you can move to the next part—turning the setting elements into creative elements. The moment a character moves, they become a creative element. In general, characters are creative elements just by being on the stage, but this isn’t always true. You might describe a character who walks off the stage without doing anything, or a character who just walks on with no other purpose. These are not super common, but they happen especially in crowds and on crowded streets. You can always promote them to a creative element, for example, a newsboy on the corner is a quaint add. If your protagonist buys a newspaper, the boy and the paper are promoted to creative elements. If the protagonist asks the newsboy a question of importance, that might move them to a plot element. If the newspaper includes important information, that moves the newspaper to a plot element. In any case, these are all for tension and then release. The tension is usually the promotion of the element.

I’m looking at setting elements and writing about their promotion. The most important point is the introduction of these elements in descriptions on the stage of the novel. Note that there is no need of a total brain dump when we write the description although the author needs to look closely at each element as it is added to the narrative.

For example, as we bring a new character either in the description or as they enter the stage, we need to express them as a setting element. As we set the stage, we describe. I won’t give an example yet, but I’ll continue to describe how we do this.

In the first place, whatever is fixed on the stage, we must begin with that. A good place to start is with big to little. The big is usually the sky, light, and conditions. This really does set the scene. I’m not in favor of telling, for example, “It was Christmas.” A better way to approach this is through showing the description, “The night was dark, and a light covering of snow covered everything as if it perfectly expressed the season. Red and green lights blinked on and off with typical Christmas decorations on each house.”

Okay, this is showing. I just showed you that it was a night during the Christmas season. I did this without telling. I used the word Christmas as an adjective and didn’t tell you the season—you imagined that part yourself. We can get deeper into this. The point is to start big and go small, but we aren’t just puking out everything at once. We shall continue with this.

There is more to this, of course.

Setting a scene is a great skill. As I wrote, we don’t just puke out the entire scene and everything in it. We should have a plan for the setting and the description(s). I recommend starting with the large and going to the small. You could also go from the important to the less important.

For example, I usually start with the sky, that is the weather, lighting, sky conditions, with some hints about the time and season. This is evident when the curtain rises. I then move to the larger items on the stage: the buildings and grounds for example. These can tell you a lot about the time, place, and season. Again, the point isn’t to tell but to show what is on the stage. I like to start with the building and the grounds, and then move the description with the characters. Obviously, the writer must get to the character or characters. This is a description too.

Note, that these are obvious things on the stage. As we move the camera to these, we describe them. Thus, the place, the main buildings, the main character(s), then we move the camera with the character(s). At some point, we have described and set the scene sufficiently to begin the action and the dialog. With the action and dialog, we can describe other characters and items as we go.

Here’s the basic rule of description. The moment we introduce something, we should describe it. I’ll get to that next.

I teach Arlo Guthrie’s method or technique for description. He might not have been the first to say it, but it makes sense to me. The first time we describe something, we give 300 words to a major character or place and 100 words to a minor character or place. This is a great rule of thumb. You don’t have to count words, but the main point is to give that much, 300 and 100 words or so worth to your descriptions.

If you notice, the rule of thumb isn’t to give 1000 or 5000 words, but 300 and 100. Reading the Victorians, some might conclude that more are better, but that means you didn’t really read the Victorians—if you did, you would know why 300 and 100 are just right and much more is too much.

If you don’t believe me, go back and reread the firstr chapter of The Mill on the Floss. I love George Eliot, but the telling and the describing for that novel is just too much. Way too much. She does better in most of her other novels, but it’s just too much. Read Arlo Guthrie’s Big Sky and see how his method works. He does a great job with description. No telling only showing.

I’ll get more into this, next.

The things on the stage of the novel need to be described, by showing. Show us with 100 to 300 words what the weather, sky, and land look, smell, taste, feel, and sound like. Show us with 100 to 300 words what the buildings and land based stuff looks, smells, tastes, feels, and sounds like. Show us with 100 to 300 words what each of the people on the stage look, smell, taste, feel, and sound like. Okay, you most likely don’t need to show us what they taste or feel like, but the others are fair game. The point is simple, just show us what we can see.

You can make normal and reasonable transitions with action or dialog to differentiate and fit the characters. For example, you can transition from a house to a character by having them open the door and walk out. Or you could have the character at the wall speak out loud or to another. Then describe them. The point is to show us what we see on the stage and to get to these descriptions in a natural and reasonable way—without telling. I should likely hunt up an example. I think I’ll bring up Shiggy from Rose again.

I’ll show it to you next and then explain it a little.

Here is more from the initial scene from Rose: Enchantment and the Flower.

When Shiggy returned to the kitchen, the girl was struggling against her shackles and the chair. She had moved it a few feet across the floor. Shiggy kicked the legs of the chair and caused it to fall backwards onto the floor. The girl went with it. She struck her hands and arms with a thud, and her head followed along afterward. That sounded like a melon hitting stone. The girl lay dazed with her legs slayed to either side of the chair and her too short dress well above her naked thighs.

The girl hadn’t made a sound. Shiggy felt a little sorry for her, but this kind of physical control was usually an indicator of a trained intel asset. That’s the last thing she needed. The girl did either have special skills, or perhaps she was just very well trained. Unless aided by glamour, usually getting out of zip tie bonds was an advanced technique, and Shiggy knew how to foil all the usual techniques.

The girl is a fighter, and this worries Shiggy. The weak and normal usually give up early. They whine and cry. They beg for mercy and they talk a lot. Shiggy is used to this and knows this. The second paragraph tells you all you need to know—the control the girl shows is usually an indicator of a trained intel asset. I mentioned before, getting out of zip ties is a trained technique as well as one of glamour. Glamour, if you remember, is the miracles the Fae can do.

Shiggy latched the girl with silver chains. Silver negates the power of glamour—that’s why Shiggy did it. She suspects the girl has some control over glamour—that makes her dangerous. The silver should negate this power and keep her confined. Notice, the girl is still trying to escape—that shows her determination and that the silver doesn’t have as much power as Shiggy would expect. A Fae being would be in a near catatonic state, at least in a fetal position because of the silver. All this makes the girl very special, and very dangerous in Shiggy’s mind. I think I’ll continue a little on this example.

Out of pity, and because she wanted to check, Shiggy flipped the chair back up on its legs and slapped the girl’s dress back down. She shook her head, the girl’s wrists and ankles, where the silver chains touched them, were covered with welts and little boils. Shiggy pursed her lips. Well, she was sensitive. Shiggy pulled back the girl’s hair, yeap pointed ears. Shiggy needed to be especially careful now. There still wasn’t a reason to push the panic button, yet.

Shiggy sucked on her teeth. The girl’s head lolled against her chest. She was still out. Not quite out cold, but she was out. Shiggy’s stomach growled. Time to make dinner.

Shiggy took the smaller bag and began to unpack it. She put butter, eggs, milk, yogurt and some other stuff in the frig. She filled one of the kitchen cabinets with dry goods. She didn’t leave anything out that would indicate the house was in use.

The cooktop propane gas kicked on right away, and Shiggy made scrambled eggs for herself with toast, butter, and jam. While Shiggy was eating, the girl’s head slowly raised. She licked her lips. Shiggy just kept eating. When Shiggy was done, she cleaned up the dishes and put them in the dishwasher. She glanced around the kitchen. Nothing showed that anyone was in the place. That was good.

Shiggy took one of the kitchen chairs and set it across from the girl, well out of range of any possible or potential attack. Unless the girl could make miracles Shiggy hadn’t heard about, there was no way she could get loose or attack anyway. Shiggy was just very cautious by nature. She hadn’t had a problems since she had been on assignment, well not since Sorcha, her boss, had allowed her to go on these unsupervised assignments. She had a few problems at first, but she wouldn’t think about that.

Shiggy stared at the girl for a few moments. She contemplated different means of getting information from her, then sighed. She might as well start with questions. First to the basics. Shiggy sat in the chair backwards to the right of the head of the kitchen table with the chairback facing the girl. She opened her official computer just within reach to her left on the table. Shiggy pulled her knife out of its hidden sheath under her arm. It was a Gerber graphite combat dagger with smooth edges on each side—perfectly balanced for throwing. Then she made sure the girl could see the pistol in its inner thigh holster between her legs.

The girl licked her lips again and blushed. She held her head high with an elegant tilt to her chin.

Shiggy held the knife in front of her and pointed it at the girl’s eyes, “I’m not about playing games here.”

The girl turned her head to the side and swallowed hard.

Shiggy tapped the handle of her knife on the chair back. It made a loud noise in the kitchen. “I’m not that adverse to you looking wherever you please, but it does help me determine whether you’re lying to me if I can see your eyes directly. You very much will want to convince me that you’re telling the truth.”

The girl’s lips trembled, but she stifled that and stared directly at Shiggy, “What do ya want from me?” Her voice was light and melodious tempered with a sharpness that sounded very interesting, and in a thick Rousay Scottish brogue that Shiggy had to think to translate.

Shiggy grinned, “That’s better. First of all, what’s your name?”

The girl raised her chin in an aristocratic motion, “I dunno why I should tell you, but it’s Rose Craigie. What’s your name?”

Shiggy ignored her question. She kept the girl in sight but turned to her computer on the table and entered the name in the database. It was securely connected via a cell backfeed to London. Shiggy frowned, “What’s your Community Health Index Number?”

“I dunno what that is.”

Shiggy pointed the knife at the girl, “Every child in Scotland is given such a number. When were you born?”

“I dunno.”

Shiggy almost called her a liar. She held her temper, “How old are you?”

“I dunno.”

“Really? How old do you think you are?”

“Me gram and my paps died eight winters ago. Me ma left soon after. Me da died five winters back.”

“And you have no idea how old you are?”

The girl, Rose, shook her head.

“What was your father’s name?”

“James Sinclair.”

“Why aren’t you Rose Sinclair?”

The girl lowered her head slightly and blushed, “He said I wasn’t worthy of it. My mother gave me my name. She claimed to be a Craigie. She called me Rose Craigie.”

Shiggy let out a loud sigh, “I’m not calling you a liar. I can find a James Sinclair and his parents in this parish. I can’t find your name, love. What’s your mother’s full name?”

Rose’s mouth worked a bit, “I was never sure if she was telling me the truth, she called herself a Desert Rose. Desert Rose Craigie. Me da called her Rose.”

“Where did she live?”

“We lived in the barn at the back until gram and paps died. She left soon after. I told you.”

“I remember. So, on to the big question. Why are you here?”

Rose glared at Shiggy and spat out with an encompassing twist to her shoulders, “This is my house. Why shouldn’t I be here?”

“Tisn’t your house. I know the owners. They rented it to me. They had it refurnished and redone not that long ago.”

The girl trembled with rage, “It is my house. It’s the only place I’ve ever known. Me da left it to me.”

Shiggy sat back. She interpreted from her computer, “Your da mortgaged the house and spent all the proceeds. When he died, the house went to the bank. The bank sold it. Your da left you as much of this house as he left you his name.”

Rose cursed in Scottish Gaelic. She cursed again, “Then what am I to do? What’s to become of me?”

Shiggy leaned forward again. She tapped her teeth with her dagger. She gave a couple of thoughtful sighs. She looked Rose up, then down, then she asked, “Can you cook?”

Rose sucked on her bottom lip, “Not well. My gram taught me the basics. I cooked for my father until he died.”

“You cook pigeons.”

“I can cook whatever I can get to eat.”

“That’s interesting in itself. Let’s say I brought you chicken and rice, could you cook it?”

“I probably could. I’ve cooked chicken, and I’ve cooked rice before.”

Shiggy chewed her lip, “Have you been to school?”

“Gram and paps said I should go, but da would never let me. He said I was not to let anyone see me.”

“That’s very interesting too. No education at all. That would make you pretty useless.”

Rose squared her shoulders, “I can read and write. I’m not uneducated.”

“Really?”

“Me gram was a teacher. She taught me to read and to write. She taught me some maths too, but da said it wasn’t necessary to teach such things to girls.”

“It is very necessary, that is maths. Can you learn? Do you like to learn?”

“I read all the time.”

“That’s good.” Shiggy thought in silence for a long while. Finally, with a smile she pronounced, “So, Rose Craigie, I have a proposal for you.”

The girl looked up at her.

“I am going to live in this house for a time. I have a job to do while I’m here, and I don’t want to have to deal with cooking, cleaning, and all those other domestic details. Can you cook, clean, and look after this place while I’m working?”

“It’s my house.”

“Listen, love, it isn’t your house. If wishes were fishes and all that, but they aren’t. The other option is that I…well here are the other options. I could turn you over to the local constable. I suspect that would not go very well for you. You aren’t registered as a citizen of these isles. They might try to deport you.”

“I understand deport. You actually think they might try to send me to some other country.”

Shiggy smiled very broadly, “It’s always possible, but I suspect they would go to my second option first. That’s to put you in the Looked After services. They’ll put you away with a nice family, perhaps, who will look after you. After you time out in a few years, what will you do? You have no education, no prospects, nothing. I can offer you a little bit more than that.”

Rose glanced down at the floor, “What do you really offer me?”

“Don’t you want to hear option three?”

“Now, you’re just taunting me.”

“I am taunting you. You’ve already caused me some difficulties. You’re in the house I borrowed, and I’m trying to figure out what to do with you.”

“What’s option three?”

“It’s really not up to me, but there’s always the Youth Court. You are trespassing and have been for a while from what I can tell.” Shiggy let the words out slowly, “You could go to prison. They would feed and educate you there.”

The girl visibly trembled, “I dunna wanna to go to prison. I must always keep the soil under my feet.”

“Look at you, there’s soil all over your body as well.”

Rose scowled, “I ask you again. What do you really offer me?”

“Here it is, sweety. I already told you, all you need to do is take care of this place while I’m working. Cook, clean, keep an eye out. That’s all.”

“What about after that?”

“Well, love, I can’t just leave you here. If you accept my offer, you’re on probation. If you really please me, then we’ll see. You can think about my offer as long as you want.” Shiggy stepped to the back door and checked the lock and her sensors. She turned off the lights in the kitchen and walked toward the dining room door.

Yes, we are moving from description and stage setting to action and then finally, dialog.

Perhaps I’ll move over to my science fiction novels. I need to write a new one of them.

The most important thing for the scene is developing the entertainment in the scene.

I’ll write more tomorrow.

For more information, you can visit my author site www.ldalford.com/, and my individual novel websites:

http://www.sisterofdarkness.com

fiction, theme, plot, story, storyline, character development, scene, setting, conversation, novel, book, writing, information, study, marketing, tension, release, creative, idea, logic